Recently, I've been reading book after book, trying to find one that parallels my own. When you embark on a project that documents your family's history of mental illness, finding a role model that deals with the ugly topic ain't easy.

Recently, I've been reading book after book, trying to find one that parallels my own. When you embark on a project that documents your family's history of mental illness, finding a role model that deals with the ugly topic ain't easy.

At long last, I've found one that serves as an inspiration for dealing with turmoil that's sparked by fear, change, longing, depression and illness.

"The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit: My Family's Exodus from Old Cairo to the New World,"by Lucette Lagnado, speaks of a family that came together quickly - an elaborate gambler named Leon Lagnado, the author's father, who married Edith, a quiet and reserved librarian who was born to riches until her father left the family.

The family stayed together and survived, though barely. They were tested constantly, and the central character - Leon, the man who liked to wear the sharkskin suit - died as a broken, physically handicapped man (much like my mother).

But there are lessons to be learned here. Despite the family's pitfalls, the family presevered for the sake of the children and for the sake of themselves.

It started at a restaurant, where Leon met Edith and her mother, Alexandra, who was overprotective but gave her blessing to the union. This is a restaurant where Leon, a devout Jewish man who likes to party, frequently went; but on this day, he caught Edith's eye and sent her a note.

He successfully courted her and they got married, quickly, beginning a life of hardships and moving around that eventually landed them in New York. Leon sensed a bad omen when the jewels on Edith's ring are stolen by her brother just before the wedding. But the wedding moved forward, anyway, because he viewed it as the right course for his life.

The book looks back at how Leon was a bit of a playboy, staying out nights to the horror of his mother, Zarifa. She had already lost children - to death, and one who converted to Catholicism and became a priest.

Leon liked to gamble and be with the "ladies," but he resisted to the idea of settling down. He also was a broker who didn't have a steady job but bought and sold everything. The only time he settled down was when it involved religion, and he was a deeply devout Jewish person who went to temple every day to pray.

World War II changed his lifestyle, with the Nazis bearing down on Egypt. Jews thought they would be killed. Then the British routed the Germans and that gave people hope. It also made Leon rethink his priorities, and that's what led him to Edith.

After they married, they were happy, at first. They even took care of a relative who had pleurisy. But then Leon eventually resumed his old habits, even as Edith gave birth to a girl, Suzette (whom Leon initially rejected because he wanted a son) and two boys, Cesar and Isaac. Leon's beloved mother, Zarifa, died around the same time.

Alexandra, Edith's mother, became more involved in the household, but things got worse. Edith gave birth to another Alexandra, but it was determined that both she and the baby, as a result of nursing and the passing of an infection, were sick.

Edith lived; the baby died after nine days. Edith then became hysterical and blamed the situation on Leon. The marriage then began to fall apart just as Egypt changed, with President Nasser pushing out the king, taking control of the country, empowering the country's Arabs and Muslims and encouraging Jews to leave.

Alexandra, Edith's mother, then deteriorated. She started to become demented. She never lived down losing her own blue-eyed son whom her husband, Isaac, had sold to other people before leaving her. She was constantly looking for the child, even though he was long gone.

Eventually, "Lou Lou," the author, was born. For the family, she was almost like a replacement for Alexandra and the family grew closer again. But the Jews still felt threatened - especially when Britain, France and Israel invaded Egypt in the 1950s Suez crisis.

Even though Egypt won, Leon's family realized they had to get out. A part of the family, including Alexandra, left for Israel first. Leon, meanwhile, was afraid to go there right away out of fear that Lou Lou wouldn't be able to handle the heat and decrepit conditions.

The family stayed in Egypt for a while. They procrastinated. They didn't really want to go. But things became more tenuous; culture and diversity was taken out of the schools. Cesar learned how to shoot a gun.

Leon, meanwhile, bonded with Lou Lou and her cat. They enjoyed sitting with each other and staring out into the street while he taught her Arab languages - a necessity in the evolving culture and demographics of Egypt.

Then Leon became seriously injured while walking to the temple. He broke his leg. A pin was inserted, but the pin eventually broke. He lived the rest of his life with a limp that only got worse.

Later, Lou Lou developed cat scratch fever and the family was at a loss. They didn't know how to deal with it, and it delayed their departure from Egypt. It finally subsided after she and her father searched for a cure, and they went through a religious ritual. But this illness - coupled with her father's physical deterioration - became a lingering theme in her life.

The tipping point for leaving Egypt happened when Suzette was arrested - for apparent prostitution, though the charge wasn't true. Leon sprang her loose, but he knew this was the end of their time in Egypt. They packed everything up and headed for France, and they were forced to leave behind their most expensive possessions - including Lou Lou's beloved cat. With Nasser taking control, they were subjected to live a more socialistic lifestyle.

In France, they lived an impoverished lifestyle. They then looked for a new place to live for the long-term. It came down to Israel or the United States. Then they learned that Alexandra had died - a devastating blow to a family that was protective of her, and protected by her in her younger years.

Instead of going to Israel, they decided on the United States. But this process took a while because the human rights and customs people were afraid that Leon was unemployable.

In the meantime, the family grew more accustomed to French life. Edith enjoyed taking long walks to the playground with Lou Lou. Cesar did odd jobs and enjoyed the nightlife. They held on until the family's transfer was approved - even though Lou Lou's bout with what appeared to be Scarlet Fever held things up.

They went to the United States aboard the Queen Mary. Once in New York, they stayed in Manhattan before moving to Brooklyn where other Egyptian Jews lived. Suzette, constantly at odds with her father, moved to Queens and eventually to California.

Leon, meanwhile, acclimated to the life and finds a temple. He bonded with Lou Lou, again, because she needed to learn Hebrew (something girls never did). Edith, who drifted further away from Leon and even once threatened divorce, found a temple that was not so old and stodgy.

Lou Lou continued to bond with Leon, who couldn't find real work. He sold fake ties, and Lou Lou accompanied him in Manhattan as he made his rounds. They walked around, making pennies on the sales. Lou Lou, meanwhile, always sat and stared quietly, watching every move Leon made as he tried to convince Manhattan shoppers that the ties were no worse than Ralph Lauren.

At the same time, Leon became physically worse, but he did everything he could to relive Cairo and the life he had when he was a dominant physical and financial force.

Italian immigrants moved onto their Brooklyn street, and they forced the family to move to another part of Brooklyn, Lou Lou says. There, the family - led by Lou Lou - got into an argument with the landlady, and they had to move again. They couldn't get settled.

They were poor, and Lou Lou grew up as an impoverished soul. But just when things looked up, they went down again. Lou Lou was diagnosed with Hodgkin's Disease; a reversal of the conventional wisdom that she had a recurrence of cat scratch fever. The family was devastated. Lou Lou opted for radiation, possibly going against family wishes. She wouldn't be able to have children.

The family lived out the 1970s, which Lou Lou called a "wretched" decade, surviving on the minimum. In the 1980s, her father developed dementia and housed himself at a Jewish hospital, while her mother suffered strokes and went to another hospital. Lou Lou visited both but found the experiences to be excruciatingly painful.

Finally, around 1992, Leon died. Her mother died a year later. Lou Lou was welcomed to pray at the memorial service for her father - going against custom, to allow a woman to pray. But she viewed herself as Leon's life observer - his shadow - so she did what was her father's favorite custom: Kneel at the temple, and pray.

Lou Lou went back to Cairo in 2005, and visited the old house. The same family that bought the house when Leon's family left was still there. Lou Lou felt good about seeing the big rooms where she spent time as a young child, and often thought about what her father - the man who wore the sharkskin suit - would feel like if he were there, too.

But she knew he was there, in spirit, pushing her to discover and learn how the family overcame trouble and heartache. And as I embark on my own project, I feel like my mother is there, too.

Tuesday, December 30, 2008

A family that survives is a family that inspires

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

3:56 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: COPING with depression, COPING with general mental health issues

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

Keep your holiday cheer at this time of year

The holidays are portrayed as a happy time of celebration. But it's not true for everyone - especially those who have mental illnesses, and even more so in today’s economic climate.

The holidays are portrayed as a happy time of celebration. But it's not true for everyone - especially those who have mental illnesses, and even more so in today’s economic climate.

One of every four residents has a mental illness, such as depression or anxiety, which can be exacerbated during the holiday season and further intensified in reaction to financial stress, mental health professionals say.

Regardless of the time of year or the economy, it is critical to manage mental and physical health, recognize signs of mental illness and seek help when needed, professionals say.

Anyone could experience holiday blues, especially if they experience high levels of stress. During this time of year, stress is commonly related to having unrealistically high expectations for the holidays, said Debra Wentz, chief executive officer of the New Jersey Association of Mental Health Agencies, Inc.

"But this year, it could be even worse because of the turbulent economy,” she said. “It is vitally important for everyone to take steps to manage their stress levels, which can greatly impact both mental and physical health.”

Stress can be reduced by managing what can be controlled. For example, expenses, such as gifts and entertainment, can be reduced. Healthy practices, such as exercising, eating right and getting enough sleep, are also helpful in managing stress, in addition to offering many physical health benefits, professionals say.

Stress and depression can also be related to increased use of alcohol or drugs, especially for individuals who are in the early stages of recovery from addictions. The holidays, with the accompanying stress or social more situations, can also lead to increased drug or alcohol use, professionals say.

Professional help may be needed if any of the following signs become evident:

- persistent sad, anxious or “empty” mood;

- changes in sleep patterns;

- reduced appetite and weight loss, or increased appetite and weight gain; and

- loss of pleasure and interest in once-enjoyable activities; restlessness or irritability.

It is important to realize that most of these symptoms also indicate holiday blues, professionals say. However, holiday blues will dissipate when the season ends and people return to daily routines and no longer experience holiday-related stress. By contrast, depression is indicated by these symptoms lasting for two weeks or longer.

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

8:08 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: COPING with depression, COPING with general mental health issues

Friday, December 19, 2008

The Texas time warp is alive and kicking

For more than a century, thousands of mentally disabled Americans were isolated from society, sometimes for life, by being confined to huge public hospitals.

For more than a century, thousands of mentally disabled Americans were isolated from society, sometimes for life, by being confined to huge public hospitals.

In at least one place, they still are, according to The Associated Press.

Texas has more mentally disabled patients in institutions than any other state, and the federal government has concluded that the state's care system is stubbornly out of step with modern mental health practices.

Critics allege that Texas remains stuck in an era when the mentally disabled were hidden away in large, impersonal facilities far from relatives and communities, according to The Associated Press.

"In Texas, it's like a time warp," Jeff Garrison-Tate, an advocate who wants to close the 13 hospitals called "state schools" and move patients into group homes, told The AP.

For the third time in three years, the criticism has attracted the attention of the Justice Department, which on Tuesday accused Texas of violating residents' constitutional rights to proper care.

Investigators found that dozens of patients died in the last year from preventable conditions, and officials declared that the number of injuries was "disturbingly high."

In addition, hundreds of documents reviewed by The Associated Press show that some patients have been neglected, beaten, sexually abused or even killed by caretakers. Inspection reports also describe filthy rooms and unsanitary kitchens.

Many of the nation's mental hospitals were first built in the 1800s, when they were often called insane asylums. But by the 1960s, most experts concluded that patients fared better in smaller, community-based settings.

The American Institution on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities says large care facilities - usually those with at least 16 residents - "enforce an unnatural, isolated, and regimented lifestyle that is not appropriate or necessary."

Because of those concerns, eight states have abolished large institutions for the mentally disabled. Another 13 states closed most of their largest facilities, leaving just one open in each state.

But Texas has remained "the institution capital of America," said Charlie Lakin, director of the Research and Training Center on Community Living at the University of Minnesota.

The 13 facilities in Texas house nearly 5,000 residents - more than six times the national average, according to The Associated Press.

On a per-capita basis, Texas has 20.4 people per 100,000 in large institutions, Lakin said. The national average is 12.2 people.

Other states with large populations such as New York and California - which have rates of 11.2 and 7.5 people, respectively - rely far less on large institutions.

Federal law requires the mentally disabled to be treated in "the most integrated setting" possible - a factor that led to the Justice Department rebuke of Texas.

Laura Albrecht, a spokeswoman for the Texas Department of Aging and Disability Services, said the agency is expanding community-based services. Texas officials say keeping the facilities open is a matter of preserving as many treatment options as possible.

But critics allege that "warehousing" patients in large institutions invites abuse. Patients are isolated from their families and communities, making regular contact with loved ones more difficult. And caretakers often get overwhelmed by the large numbers of patients, Garrison-Tate said.

In Texas, officials verified 465 incidents of abuse or neglect against mentally disabled people in state care in fiscal year 2007. Over a three-month period this summer, the state opened at least 500 new cases with similar allegations, according to federal investigators.

An AP investigation earlier this year revealed that more than 800 state employees have been fired or suspended since the summer of 2003 because they abused, neglected or exploited mentally disabled residents.

And in the one-year period ending in September, as many as 53 deaths in the facilities were due to potentially avoidable conditions such as pneumonia, bowel obstructions or sepsis, the Justice Department said.

Some families tell horror stories of their loved ones in the state facilities. For instance, Michelle Dooley said her son spent three months in the Austin State School, which she described as a place of "dingy yellow floors and patients running around without any clothes on."

During his time there, he refused to leave his bed and often languished in his own excrement, she said.

Dooley eventually moved her son into a group home in Denton where treatment costs average about $50,000 per year - roughly half as much as the costs at state schools, Garrison-Tate said. Medicaid often picks up most of those costs.

"It was just horrible," Dooley said. "If he goes back to a state facility, he will shut down and die."

At the San Angelo State School, inspection reports from 2007 took note of scuffed walls pocked with holes, rotting food, dirty kitchens, broken furniture and missing shower curtains.

More seriously, two employees were fired after throwing a resident into a pool while he was wearing a restraint jacket. The employees had made a bet with the resident that he would be unable to dunk another resident under water. When he lost the bet, the employees restrained him and threw him in the water, according to the reports.

Other families say they are happy with the state care.

Neil Davidson said his daughter Susan, who has cerebral palsy and is mentally retarded, has flourished during her 10 years at the Lubbock State School.

"I'm very impressed with the level of care she has received," Davidson said. "As far as I am concerned, it's Mr. Rogers' neighborhood. Everybody is looking out for everybody else."

A visit to the Denton State School, the largest in Texas, reveals a sprawling campus spread across well-kept lawns. Superintendent Randy Spence described the place as a "happy, homelike atmosphere."

"The vast majority of our employees love the people they work with," said Cecilia Fedorov, another spokeswoman for the Department of Aging and Disability Services. "They think of them as extended family."

But Denton is also the site of Texas' most notorious case of state school abuse.

In 2002, a care worker repeatedly kicked and punched a resident in the stomach and groin. Haseeb Chishty nearly died after that beating. He is now confined to a wheelchair and unable to feed himself or use the bathroom.

"It got to the point where it was fun beating him, torturing him," said former care worker Kevin Miller, who is now serving 15 years for aggravated assault.

In a statement videotaped by Chishty's lawyer, Miller said he and many of his fellow care workers used methamphetamines, cocaine and Oxycontin on the job.

Chishty's mother filed a lawsuit against the facility, but it went nowhere. In Texas, government entities are all but immune from lawsuits.

Some critics want to close the state schools. But because the Texas Legislature created each one, only lawmakers can close them.

Many of the institutions are large employers in small towns, and they often pay more than other jobs in rural areas. Lawmakers fear taking action that would lead to layoffs, Garrison-Tate said.

"Even if we said we wanted to close all state schools, the community resources

aren't there at this time," said state Rep. Larry Phillips, chairman of a legislative committee studying the facilities.

Kelly Reddell, the lawyer whose client's son was beaten nearly to death, said the state is not doing right by its mentally disabled.

"The very nature of the institutional setting, I think, creates the environment for the abuse to take place," she said. "How in the world can you think this system is the best and it makes sense?"

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

8:08 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

Others countries find ways to help themselves; can we?

It has been 10 years since Bishop Gerardi was a leader in ending human rights abuses in Guatemala - a fateful act of generosity that ended with his assassination.

It has been 10 years since Bishop Gerardi was a leader in ending human rights abuses in Guatemala - a fateful act of generosity that ended with his assassination.

A decade later, we can look at that case as an example of how absolute power corrupts absolutely -- and not just in Central America, but in all countries that threaten civil liberties, including the post-911 United States. When countries threaten civil liberties, they destroy the psychological self-worth of their citizens, mental health professionals say.

Perhaps no book illustrates the abuse of power, and the ultimate triumph over it, than "The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed Bishop Gerardi?" by Francisco Goldman. Some of the human rights abuses appeared to be sponsored or indirectly sponsored by the Guatemalan government prior to Gerardi's death.

But when he died, so did the country's self-worth - until those responsible were found and jailed, giving Guatemalan citizens a much needed psychological boost. But before that happened, a cover-up that the government indirectly endorsed dragged the nation through a period of degrading limbo during which people were killed and tortured.

It should be noted that, during that time, the United States lent a tacit endorsement of the government's actions - even as Guatemala's leaders participated indirectly in the cover-up of the murder - because they were anti-Communist, according to the book.

Gerardi was not so anti-Communist, thus sealing his fate.

Two decades ago, Gerardi was deported after his life was threatened, but the wicked leaders that supported the corrupt government lost power or died. So he came back, and drew up a report that outlined the abuses.

He threw a party following the release of the report, and the bishop acted as though his life was safe - even though, deep down, he thought otherwise.

On that night after the release, others were worried when he didn't show up for other festivities and then called to check on him. When he didn't respond, people worried.

Another church leader at Gerardi's parish noted he saw a light on that was normally turned off, but was on. He went to investigate and found Gerardi in a pool of blood in the garage. Later, this same church leader - who was eager to show people the body - was charged in connection with the murder.

Sometime before that discovery, local homeless saw a big shirtless man leave the garage. Then another man gave them food that appeared to be drugged because they fell asleep more quickly than usual.

The cover-up was on.

After the murder, the church leader, known as "Father Mario," was arrested. It appeared that government and the potential suspects in the crime - all of whom belonged to the Army - were trying to blame the church or the indigents for the crime. But they also knew something that others didn't want them to reveal: an unknown witness found a license plate number on the car in the garage that led to the connection with the Army and the suspects, who were ultimately charged in connection with the crime. With that looming over their heads, the suspects appeared doomed.

But the troubles were just beginning, really. Prosecutors were biased or scared, and some left the country. Friends of the suspects tried to say the murder was a product of a homosexual tryst and they tried to pin it to the clergyman, Father Mario.

Authorities tried to re-enact the crime. They went over the scene but couldn’t match much to anything. They performed an autopsy and determined that Mario wasn't directly responsible - even though the father spent lavishly after the murder and acted indifferently toward it. Prosecutors eventually found the man - a taxi driver - who had the license plate number. Until that point, the man was continually getting death threats and he was even kidnapped once. He was considering exile.

Prosecutors eventually found the man - a taxi driver - who had the license plate number. Until that point, the man was continually getting death threats and he was even kidnapped once. He was considering exile.

Others connected to this case were either murdered or went into exile. A new judge really wanted to get to the bottom of murder, but he went into exile, too.

A break in the case occurred when independent investigators associated with the church and human rights groups found an Army man whose job was surveillance, and he kept records of what happened that night. A new special prosecutor also wanted to move forward on the case, and he found other witnesses, too. The prosecutor - who wore a bullet-proof vest and was accompanied by an army of security detail - discovered that one of the homeless people was actually an Army spy. He saw everything that was happening in the garage. He was told he might be implicated in the crime, but he went ahead and testified anyway.

The suspects were convicted, and sentenced to 30 years in jail.

Justice won, but it took more than just testimony. It took courage for people to rise against their government and determine that the best solutions to problems usually come from the people, and not from power.

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

4:31 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

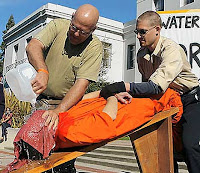

The psychology of government-sponsored torture

Based on what's now being written about the last eight years of governing, some may wonder if they really are living in the United States of America.

Based on what's now being written about the last eight years of governing, some may wonder if they really are living in the United States of America.

This not a country that tortures its people, many say. Nor is it a country that treats foreigners with disrespect. This is, in fact, the land of Ellis Island, the Statue of Liberty and other gateways that lend credence to the saying, "Give us your tired, your poor, your weak...."

But when they to read about what some describe as the foibles of the Bush administration over the past years, some view the dark, grisly emperor from the "Star Wars" movies as a better metaphor for what the United States become - or vice-versa.

A book called "The Dark Side" by Jane Mayer, which I recently read for my Columbia University Bookwriting class, may convert those who never considered themselves as extremists of the left, and never a part of the let's-throw-the-Bush-administration-in-jail for war crimes crowd, into the foot soldiers of prosecution - if what the book says actually happened.

The book not only speaks to the psychology of torture, and how it can make or break one's will. It speaks to the psychology of a country that some believe became so cynical following the Sept. 11 attacks.

The idea was that torture would work, but from the book's point of view, it really didn't. If anything, if was a re-enactment of the eye-for-an-eye mantra of the Old Testament culture that eventually led to a period of rebirth of faith and healing - but only after years of fighting and bloodshed.

The book describes conservatives who were hell-bent on expanding powers of executive branch, led by Vice President Dick Cheney, who watched those powers shrink following Watergate scandal when he served as President Ford's chief of staff.

He was helped by a what critics described as a "henchman" named David Addington. He had his own henchman, they say, a hack lawyer by the name of John Yoo, who constantly issued interpretations of the U.S. Constitution that allowed the Bush administration to subvert the law in the handling of alleged terror suspects, according to the book.

Following the Sept. 11 attacks, if you wanted to discuss national security and the handling of prisoners, you had to go through Cheney. Or Addington. Or both, the book says. They wouldn't hear any other opinions.

One of the first prisoners was John Walker Lindh, the so-called American Taliban who was beaten up because he fell in with the wrong crowd. If you believe the book, Lindh was stupid and naive. But he wasn't Osama bin Laden. He was treated as such, however, and was beaten until he was nearly dead.

The trend continued from there. The CIA and other terror-handling agencies stuck things up people's you-know-whats - suppositories and the like - if they wanted to get information, according to the book. They beat them and kicked prisoners who were held in secret prisons in countries that were supposed to be our enemies, or at the famous Gitmo prison in Cuba.

They blindfolded them and made them stand for hours on end. They had women flirt with Muslims who considered such a situation as a fate worse than death.

They were transported to parts of the globe that did not treat people very nicely, such as Syria. They were carried by clandestine planes. Some reporters did research for exposes they planned, but they didn't get very far - for whatever reason. That's probably because, the book points out, if they got anywhere at all and wrote something about, they were ignored by the reading public.

Addington and Yoo found ways around the law, justifying their actions after they happened. They didn't believe in the Geneva Conventions. They believed the president had the authority to commit toture as he sees fit.

Former Defense Secretary Rumsfeld didn't want any part of it, at first. But when Iraq war broke, he was on board. His own people, the book says, carried out his own battle plan.

That's what led to Gitmo and Abu Ghraib. Prisoners were picked up even when the government had slim evidence. Some didn't get out right away, even when they were innocent. One even died an hour after he was picked up just an hour before, suffocating after suffering a rib injury, the book says.

They adopted procedures called SERE, which taught CIA and others what happens when you torture. Psychologists assisted, but they weren't there to experiment. They were there to help the torture proceed.

Results were mixed. It became like a latter-day KGB, where torture led to more wrong answers than right answers.

Some tried to reform it, and met resistance. When the Supreme Court released a decision that effectively eliminated torture, the resistance continued.

The White House went into cover-up mode, the book says. People were brought in to reform the system. Instead, they continued to do the administration's bidding. It was either that or lose their jobs.

Led Sen. John McCain and mounting public pressure, as well as evidence leaked to the press, Congress finally did something about torture, the book says. Evenutally, Cheney fought for continuing the reversal of the Geneva Convestions, and lost. But he did manage to squirm something into the final legislation that kept executive power intact. McCain, running for president this year, let it happen, according to the book.

There is no evidence that torture has actually helped. In fact, it's only hurt. It has become the number one problem for Muslims in terms of their view of America, the book says.

Once the record becomes more evident, the chorus of opponents quite possibly could become much larger.

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

5:21 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, December 2, 2008

Homeless in Hackensack: The gift of hope (part two)

While she has plenty of detractors, Robin Reilly of Hackensack, N.J. has hundreds of supporters. Many of them are homeless, obvious, who have followed her around for years, and they know that wherever she is, their chances of getting food, guidance and a sense of morality have improved.

While she has plenty of detractors, Robin Reilly of Hackensack, N.J. has hundreds of supporters. Many of them are homeless, obvious, who have followed her around for years, and they know that wherever she is, their chances of getting food, guidance and a sense of morality have improved.

Reilly can accommodate, too, because she understands the importance of being politically savvy. That’s comes from her experience working with local hospitals and serving in the health care industry, where she learned that being a bull-in-the-china shop doesn’t necessarily phase the bureaucrats.

That’s why she invited city officials (none of them came) to join her during a service at the First Reformed Church on Court Street, just days before the Oct. 23 opening, to remember about 70 people who died since Reilly left her job as an interior designer at medical facilities to become a full-time advocate for the homeless..

At the event, Reilly faced about 75 other homeless advocates and people without a home – many of them mentally ill or substance abusers, nearly all of whom refused care at the county homeless shelters. They raised their hands during an invocation, hushed their mumbling voices and waited for Reilly to speak.

"Welcome my friends, your prayers have been answered," she told them. "We are one again."

Church members beamed as Reilly declared that the new site at the 300-year-old church will give the homeless a place to eat a snack and get regular health checkups.

"We are trying to help those in need," Ted Kallinikos, a church elder, told The Record of Bergen County, N.J. "We're trying to do what's right for the community

It will be open only from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Tuesday through Thursday; and no one will be allowed to sleep there (wink, wink, Reilly says). But it will be a 5-hour respite for the homeless who have been sleeping in abandoned lots and buildings, and in vacant lots with overgrown weeds on 10-degree days, and find themselves at Hackensack University Medical Center with their toes ready to fall off because of frostbite.

The Rev. Tim Eppolito, the pastor of Faith Reformed Church in Lodi, a sister church, said the decision to provide space was easy – without fear or remorse that they, too, may have joined the hit list that Reilly believes some Hackensack officials and police officers have conjured up and plans to use against friends of Reilly whenever necessary.

"As a non-profit organization, we minister to those who are less fortunate," Eppolito told The Record of Bergen County, N.J., who recited passages from Jeremiah in the Bible about "seeking the prosperity of the city."

For Reilly, smoothness is a rare commodity – especially when you’ve been bounced around as many times as she has. But the church ceremony was exactly what dreamed of as she fussed over paper napkins and place settings two weeks earlier. It was solemn, it was sweet, and it was successful. There was a solemn service where people tossed roses into the Hackensack River in honor of the homeless who have died.

And it was capped by Reilly recalling those who died, as well as their nicknames and clothing attire.

Later, she remembered 2001, when she shared a moment with Jerry Flanagan, a homeless person who died soon after she packed things up in her office at the Salvation Army in Hackensack. She was moving out after using the spot for the summer, and once again planned to take her homeless advocacy directly to the streets.

In that location, at the Salvation Army at 89 State St., she operated out of a 12-by-20-foot office and provided assistance to more than 1,100 homeless and poor people. She attracted the same of legion of followers who came to cry on her shoulder or sleep on a couch, back when she was an administrator at Peter’s Place and before she was fired from there, for a few hours to sober up. In just a few months, she referred hundreds of clients to hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and employers.

"I'm not working for anyone right now. I'm working for God," Reilly said at the time as she packed furniture, a sewing machine, and cans of food. Several homeless people watched, and they hugged her when she grew misty-eyed.

That time, the departure was amicable. Seven months earlier, she was fired by Peter's Place, a privately run, 25-bed shelter at Christ Episcopal Church on State Street. Reilly, who co-founded the shelter in the mid-1990s, attributed her departure to a policy dispute.

Reilly and Stephen Lyle, the commanding officer of the Salvation Army's Hackensack facility, said the two had a mutual agreement that she could use the office only on a temporary basis. But Lyle said the charitable agency needed the space for its fall programs. "Hopefully, she can find another place," he said at the time.

Already, Reilly had a plan. She would walk the streets and railroads and meet with homeless people at the Johnson Library on Main Street. She'd carry her cell phone in case she has to get assistance for them. The one thing Reilly wouldn’t do, she said, was quit.

Reilly was an interior designer who decorated medical facilities. Back then, she dabbled in homeless causes, and she was so moved by the people she met that she gave up her lucrative career to become a full-time advocate. When she worked at the Hackensack University Medical Center, she had an opportunity to see the problem, for the first time, up close.

She saw people with missing toes and thumbs hauled in on stretches quivering after spending the night in below freezing temperatures. She saw them arrive with no one standing by them as they were hauled off the ambulances or wheeled in on wheelchairs.

"I realized that I didn't want to pick out desks for doctors to make them feel better. I realized this was a lot more important," she once said. "It's an unglamorous job, but it's the most rewarding job of my life."

It was then that Reilly sought opportunities to help. But she didn’t want to just, as was suggested by hospital staff, “stuff envelopes.”

“I said, ‘No, I want to be out with the people,’” Reilly said.

As she packed the last of her boxes and bid her followers goodbye at the Salvation Army in 2001, for instance – just months before she would settle in at her State Street location –Reilly's followers crowded her office. Her desk was already gone, which freed up some room for people to sit. One man, Darryl, fiddled with a computer that he helped put together so Reilly could compile statistics. He also played harmonica, getting other clients to stomp their feet as he played away.

That summer alone, she collected more than $3,000 in donations from businesses, civic organizations, and schools, she said. But that money was all spent to buy medication and provide transportation for her clients.

"It's the kind of job where you get to be exhausted, but you say, 'Damn it, I've helped somebody,'" Reilly said at the time. "You look in the mirror and feel good at night."

After she left, Reilly said, she traveled to 178th Street in Manhattan to persuade a former client to give up prostitution. She did not succeed, but Reilly gave the woman a meal before she left. Since then, Reilly said, she has returned there and assisted other former clients whom she worries are "dying" on the Manhattan streets.

Some stayed; others followed her to State Street, and helped drag the ratty old couch with them that people sat on at Peter’s Place and the Salvation Army so they could “rest” at the State Street storefront. Hey, when you’ve been up three straight nights, afraid to fall asleep in the cold, what do you do?

Reilly called the State Street place a boutique store, and there was a collection of old lamps, lights and furniture that people dropped off, with price tags attached to them. She even had an employee to help out. But within months after the place opened, the boutiques never moved.

The cops started to notice, and began questioning her motives. Still there was plenty of “wink-winking” going on, she said. She had an ally in Hackensack Mayor John “Jack” Zisa, who saw her efforts as the one effective way to keep homeless off-the-streets. He looked the other way until he decided not to run in 2005; from there, things went downhill.

"She is one of the most sincere, if not the most sincere, homeless advocate I've ever met in my life," Zisa once said. "She works endless hours helping people."

Then, Reilly said, she was willing to "fight to the death" to protect the homeless. It was the same kind of relentlessness that contributed to her departure from Peter's Place: She said she let a woman sleep on a bench at the facility even though she was ordered not to.

Now the relentlessness is back as she opens her place at the church. City officials may protest, but she’s hoping to find another ally again – before the cops and the code enforcement officials wake up again and give her hell.

That’s fine, she says. She’s in the business of extending lives, even if it’s just for another month, another week or another day.

One such life was a woman named Jacquie. She’s been to jail 30 times, but she’s better known for her scratchy, high-pitched voice, and her habit of going into dining places, eating a meal, and not being able to pay. She’s lived in dumpsters near the Bergen County Courthouse, where she was once raped.

Jacquie has schizophrenia, and she’s been in-and-out of psychiatric hospitals. She does well for a period of time before she finds herself back on the street again, left to fend for herself.

“That’s when she seeks me out,” Reilly said.

Two weeks before Reilly’s new place opened, Jacquie popped in at the First Reformed Church. Reilly was stunned; how did she even know about this place, Reilly thought. But Jacquie was always clever, and she has a habit of popping up out of nowhere.

Jacquie handed Reilly a card. “I love you,” it said. Reilly’s face quickly turned from shock to tearful glee. She’s literally pulled Jacquie out of those dumpsters. To get a card like this, she said, made it all seem worth it.

“They moved me in with a mission and that’s a miracle,” she said.

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

4:01 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()