Outside Dick Winans’ cottage, the ocean waves splashed on the soft sand, washing up to the tourists’ bicycle tires as they peddled along the Bay Head, N.J. waterline. Along the beach, men dressed in suits, hats and ties as they spread out their blankets and pulled food from picnic baskets. Some would arrive at sunrise, enjoying the orange glow that wrapped around the Bay Head horizon every morning.

Outside Dick Winans’ cottage, the ocean waves splashed on the soft sand, washing up to the tourists’ bicycle tires as they peddled along the Bay Head, N.J. waterline. Along the beach, men dressed in suits, hats and ties as they spread out their blankets and pulled food from picnic baskets. Some would arrive at sunrise, enjoying the orange glow that wrapped around the Bay Head horizon every morning.

In 1933, Dick spent his summer weekends there, jumping into the waves and swimming out so far that the lifeguards had to whistle him in. He often walked door-to-door carrying buckets of fish he bought at a nearby wholesaler, and then selling them to the tourists who rented the six-bedroom mansions and the small, three-room cottages that lined the beachfront. Some politely declined; others pitied him and obliged.

Dick, then 20, dreamed of attending Princeton University, even though he knew his family couldn’t afford it. He wanted to be a successful businessman, even as his father suffered through the worst effects of the Great Depression, losing thousands of dollars in the stock market crash and struggling to keep his insurance-broker business afloat.

But the shore was Dick’s refuge, a weekend escape from a life that he often described as unsettled and uneasy. It would be his one constant, the place that offered few surprises as his family moved three times during the early 1930s, eventually settling in the small, but busy community of Hightstown, N.J. that was 50 miles north of Bay Head.

In Dick’s life, the beach would be an enduring symbol, serving as a resting place for his mother, Grace, as she recovered from the effects of a stroke. Its elegance would remind him of what his family once was: A prominent, successful colonial family who were among the first settlers in Elizabeth, N.J. Ultimately, the shore would become his life’s saving grace, helping Dick move past tragedy that forced him to put his ambitions on hold and move once again.

On July 12, 1933, a month after his high school graduation, Dick departed Bay Head and left behind his ailing mother so he could be with his father, Edward. Earlier in the week, his father gave simple, but short instructions: Arrive at the South Main Street house at 3 p.m. on Wednesday. No reason was given; no plan was offered. Just come home, Dick was told.

Once there, Dick discovered what his father had planned: Edward was sitting on a chair that was close to a gas range, his arms folded and his head tilted over, but still wearing his eyeglasses. Cotton batting and paper had been stuffed into the home’s cracks and the keyholes, blocking anything from seeping out.

Edward Winans, 62, had been dead for 24 hours.

Five years earlier, his mother and brother died the same way, suffocating when gas burners were left on.

Unlike them, Edward’s would be labeled a suicide, a victim of financial troubles brought on by the Great Depression. He would be among the 17 for every 100,000 Americans who killed themselves during the 1930s. Like so many others, he chose to kill himself rather than get rid the car, the beach cottage, the private school and the stylish clothes that made the Winans family feel whole.

Once, the Winans were symbols of consistency and stability. The family settled in Elizabeth, N.J. during the 17th century, and stayed in the same South Street neighborhood – just blocks away from City Hall and the library – for nearly 200 years. Dick’s grandfather, Elias, fought for the Union in the Civil War before he was married and raised a family of four children, beginning in the late 1800s. Dick often told others that Stephen Crane, the author, was a cousin. Both the Winans and the Cranes were among the original founders of Elizabethtown back in the 1600s.

After Elias died of heart disease in 1903, at the age of 62, Dick’s grandmother, Lydia, moved with her son, Frederick, into a small South Street shingle house in Elizabeth that was divided into two, three-room apartments. The quiet pair lived there for 25 years, maintaining a polite but rarely social relationship with those who lived in the long row of neighboring apartment buildings that were rising up in Elizabeth’s busy downtown.

On Oct. 5, 1928, a neighbor detected a gas odor coming from Lydia’s apartment. He called police, who quickly arrived with an ambulance and a doctor. Forcing their way in, they opened the door to the kitchen and adjoining bedroom.

There, they found Lydia on the couch, and Frederick on the floor. Their dog, who had been heard barking a day earlier, was lying in the center of the room, lifeless. All three had been dead for several hours, their bodies heavy and rigid.

In the kitchen, gas was flowing from a burner, and its smell filled the kitchen and the bedroom. No note was left. No motive was found. The police ruled it accidental, even as neighbors wondered: Why did they die in the daylight with the door shut?

At the time, Edward was 57, living with his family at the Stacy Trent Motel in Trenton, a 10-story high-rise in city’s downtown. He had been struggling for years to make his insurance business profitable, hoping to find the success that would finally anchor his life.

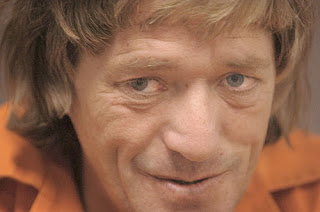

Right: Dick Winans, my grandfather

Edward was raised in Elizabeth, and he and Grace settled there before moving to Asbury Park, where Dick was born in 1913. At one point, Edward left the family and worked on a cattle ranch as a cowboy in Wyoming, hoping to raise extra money so he could come back to New Jersey, and find a permanent home that his family could afford. But he departed Wyoming after only a year, returning once he realized that he wasn’t cut out for ranching and branding.

Edward was an anxious man who was never satisfied with the money he had, the family he cared for or the job he worked. With Dick, he was distant, allowing his son to develop a much closer relationship with his mother, Grace. She kept him out of school until he was 7, choosing to tutor him while the family moved from town-to-town. Grace also taught Dick how to cook; his “specialty,” he liked to say, was pineapple upside-down cake.

But as Dick grew older, Edward became concerned. His son had little interest in sports. He joined no clubs at Peddie, an exclusive private high school in Hightstown where Dick enrolled before his sophomore year. He had few, if any friends. Edward worried, in particular, about Dick’s masculinity. He sent him to boxing lessons, hoping the experience would toughen him up and win him some friends.

But Dick still chose to keep to himself while at school, and continue cooking with his mother at home. In his high school yearbook, when each student was asked to describe themselves, Dick wrote: “An innocent, retiring floweret.”

During the Great Depression, Edward found himself working constantly, hoping to replenish the money he lost. Despite their financial worries, the Winans family sought to fit in, buying clothing for Dick that would match what the Bay Head wealthy were wearing – as well what was popular among the high-achieving, high-income-level study body at Peddie, from which Dick graduated in June 1933.

Edward chose Peddie for Dick, impressed with its demanding curriculum, as well as its brick-and-stone buildings and ornate rooftops that gave the campus a Princeton-like aura. He compelled Dick to wear shirts with high collars, silk ties and knickers, giving him a classic look that rivaled any of the shirts, shoes and socks worn by his fellow students.

Sending Dick to Peddie was also a move toward stability. Yet, while Dick was there, his family moved twice, relocating from Trenton to Lawrenceville before settling on a Victorian house on South Main Street, across the South Main Street from Peddie. There, the Peddie classroom building was only a two-minute walk away. The family’s home was part of a string of Victorian-era houses that had five or more bedrooms, nearly all of them built in the mid-19th century.

As the family struggled with illness and financial problems, Dick showed up for class photos looking sullen, unsmiling yet determined. In the school’s yearbooks, other students offered several lines of observations and aspirations about their time at Peddie, quoting Plato and Aristotle. Dick wrote only of his one goal: Princeton.

During the summers, Dick often drove his mother to Bay Head, hoping the warm sea air would somehow help her recovery. There, Grace was conscious and alert, though she slowly lost her ability to walk. At the cottage, Dick would often pick her up and carry her to bed.

As the Great Depression lingered, the people of Bay Head still wore their expensive knickers and wide-brimmed hats as they walked or rode bicycles along the shoreline. To Dick, the atmosphere made him feel elegant and wealthy. He often went for long walks along the Boardwalk that extended into Point Pleasant Beach, adoring the sunrises that glistened on the water. The area was surrounded by an ocean, bay and canal, magnifying the orange glow that came from the sunlight.

By 1933, however, Bay Head became a place that Edward could no longer afford. His money was virtually gone; yet he kept the car Dick used to drive his mother to the shore. Edward refused to buy a home, worried that he never knew where he was going live next. With his insurance business nearly bankrupt, he didn’t want to get wrapped up in a long-term mortgage that couldn’t pay off. Still, he continued to pay the rent at the cottage, believing that it stabilized his family better than any job could.

He also kept Dick in Peddie School, where tuition was more than $250 a year, even as other private schools – particularly Catholic schools – charged less than half the price.

When Dick’s father summoned him home, on July 12, 1933, he didn’t say why. Dick often argued when the reason he got, from his point-of-view, was insufficient. Others called Dick stubborn and unwilling to accept contradiction or change. This time, however, no reason was apparently given. This time, Dick couldn’t argue what he didn’t know.

That day, the sky was cloudy, but the 70-degree temperatures made the air feel cooler-than-usual. Despite the threat of rain, not a drop fell as Dick made the hour-long car trip back to Hightstown, passing by the row of small shops and markets on North Main Street that catered to the local farming community. Had Dick stayed in Bay Head, he may have enjoyed a sea breeze that broke a recent hot spell, when temperatures approached 90 degrees. Instead, he was in Hightstown, where the air was still, smelling gas as he stood a few feet from the door of his house.

He turned around and hustled across the street, heading toward the Peddie classroom building where he found the assistant headmaster, Ralph Harmon, and asked him to help investigate.

Dick often relied on the Peddie faculty for help. He could trust them, and some of the faculty acted as surrogate fathers to students who lived on campus and felt homesick. Getting them to help was logical, he believed, and never impulsive. In this case, Harmon was a natural find – he was a trusted math teacher to whom the Class of 1932 dedicated its yearbook. On July 12, 1933, Harmon readily left his place and followed Dick to his front door.

They opened it, and followed the odor the kitchen. There, they found Edward.

Weeks later, his Princeton plans on hold, Dick did the one thing his father could never bring himself to do: He sold everything off, dumping the Bay Head cottage, the Hightstown house and all the furniture inside.

He then moved with his mother to Florida, enrolled at the University of Miami and gave his mother a gift as her health continued to decline: beach sand, warm air and sunrises on the water.

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Paradise revisited, then lost (the story of my grandfather, part I))

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

8:57 AM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: COPING with dual diagnosis, COPING with obsessive compulsive disorder, COPING with suicide

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Days and nights with the bored

Don Cardinali dug his fork into a heap of pasta that smothered his chicken, and swirled the noodles into the puddle of tomato sauce on his plate. His eyes were a glazed white. His mouth opened wide for each bite, emitting an odor that smelled like a tube of glue.

Don Cardinali dug his fork into a heap of pasta that smothered his chicken, and swirled the noodles into the puddle of tomato sauce on his plate. His eyes were a glazed white. His mouth opened wide for each bite, emitting an odor that smelled like a tube of glue.

A few bites later, he pulled up a pile of pasta, clamped it with his knife and fork and shoved it so hard into his mouth that he snapped his dentures off his gums. “Holy fucking shit!” he yelled, drawing some looks from the others at the Cedar Lane Diner in Teaneck. He set down his utensils, refastened his teeth and resumed eating.

Then Cardinali, 53, pointed at the chicken filet on his plate.

“Want some?” he asked, his new, oversized but shiny white teeth jutting out from his wide grin.

For once, Cardinali, who suffered from bipolar disorder, was happy. Just a month earlier, in December 2004, he was eating most of his food with a spoon. He had to wait in meal lines that were a half-hour long at the Bergen County Jail, where he was locked up, again, on drug charges. Other inmates stole his food while mocking his shoulder-length, blonde hair, calling him “gay” or “fag.” After the watery oatmeal or the runny eggs was slopped onto his wooden tray, Cardinali would grab four honey buns, and stuff them in his armpit. Then he would sit at a table, alone, shove the rolls into his socks and save them for bedtime.

This was his seventh jail stint and, quite possibly, his worst. In one incident, Cardinali screamed at an inmate who routinely taunted him, compelling the corrections officers to restrain him and send him to lockdown for three days, where he was prevented from having contact with other prisoners.

He also was thrown out of a Bergen County program that provided guidance to prisoners with mental illness. The objective of “jail diversion” was to get the well-behaved prisoners with schizophrenia and other disorders a speedier release – if they showed promise that they wouldn’t again break the law – and provide guidance to them once they’re on their own, looking for a job. Cardinali initially agreed to play along, going to therapy sessions and agreeing to be interviewed for a potential early release. But his erratic behavior, coupled with his history of relapse, did him in.

Desperate, he called his family, friends and attorneys. The only one who answered was his mother, Agnes, but she wouldn’t talk for more than a few minutes. Then he’d ask for his sister, but she wouldn’t even come to the phone. Both his mother and sister had restraining orders against him.

“He’s a no-good drug addict. If he gets out, he can’t come home,” said his sister, Diane. “He soils the family name.”

Cardinali had no hope of getting out before July 2005, when his 1-year sentence would be finished. His next court date was Jan. 28, when he was supposed to face state Superior Court Judge Eugene Austin. Even if he had been a model prisoner, however, he did nothing to help himself get a job, transportation, housing or anything that could help secure an early release.

“I just haven’t been able to call anybody to help me out,” he said. “I had been waiting to use the phone at the jail, but there was a bunch of guys waiting to use it.”

On Jan. 28, at the court hearing, his attorney, Diane D’Alessandro, spoke for him. She told the judge he had a job, a shelter to go to and a ride to take him there. She said he would stay clear of drugs, stay out of trouble and stay clean. Cardinali admitted later he couldn’t believe what he was hearing. “I just nodded along,” he said. “I wasn’t going to argue with her.”

He was set free.

One the way out of jail, Cardinali hitched a ride to the Bergen County shelter. That night, he slept in the back of a delivery truck. For the next month, he would alternate between the shelters – as long as they had room – and the trucks parked in front of the Bergen County Community Action Program’s shelter on Orchard Street in Hackensack. He would wear the only clothes he had, or had access to. He got money for a meal from anybody he could, usually begging for a few bucks so he could eat at McDonald’s. And, as he did just before lunching at the Cedar Lane diner in February, Cardinali would spend much of his time roaming the streets, squeezing roofer’s glue into a plastic bag, covering his mouth and sucking in the fumes.

Even as his life of hardship continued, Cardinali sat at the Cedar Lane Diner in February 2005, and found reason to smile, even if his slippery dentures made smiling a struggle. Finally, he found something that worked for him.

He lied.

“I’m an addict. I’ve had a relapse here and there. But I’ve been working on recovery since 1981. I have a lot of support outside,” Cardinali said after his release.

Still Cardinali had a plan. He would beg for money from friends he hadn’t seen in a while. He would try to reconcile with his mother, he said, even with the restraining order against him. He wouldn’t have to rely on the drugs that the jail provided and did little to relieve the symptoms of bipolar disorder. Instead, he had his glue and, if he could ever find the money, he would buy heroin, too.

If anybody asked, Cardinali would tell him he’s fine. He was suspicious of the jail diversion program, anyway. He was afraid he’d be labeled as “mentally ill,” and even if he did get an early release, he’d have a hard getting a job. Now he could live his life, and pretend that all the things that brought him down – his temper, his rap sheet, his illness – don’t really exist.

Cardinali’s main mission was to prevent what happened on July 29, 2004. That day, Cardinali was sweating as he walked the sidewalk in Palisades Park. He was wearing a mesh hat, a sweatshirt and a thick pair of jeans, the only clothes he owned. He walked about two miles from B&B Upholstery, where he did occasional odd jobs, to Valley National Bank, just over the border in Ridgefield, because he wanted to see if his Social Security check had cleared.

But the heat was getting to him. So he reached into his left shirt pocket, pulled out a tube of roofer's glue and squirted a half-inch drop into a plastic bag. Then he put the bag over his mouth, and breathed in, deeply. He removed it, and looked straight ahead. The street was spinning. He stumbled a little, and nearly fell down, but he quickly straightened himself up.

Cardinali walked over to the bank, and headed straight to a teller. He was afraid that he was too high to talk, so he pulled a bank deposit slip and wrote the teller a note. The teller’s eyes nearly crossed as she struggled to decipher his writing. When she told him she couldn’t read it, he grabbed the paper and stormed out.

Outside, he stood in front of the bank window and, again, squirted glue in a bag, and then breathed in the fumes.

Another bank teller saw him, walked over to the alarm and pulled it. Minutes later, three police cars pulled up, and surrounded him. The officers got out of their cars, kneeled behind doors and drew their guns.

Cardinali dropped his bag. He stood on his toes, and raised the other leg high in the air. He later said he felt like the Karate Kid, the homeless version.

“I know Tai Chi!” he yelled.

Three officers ran up to him, cuffed him and pulled him to the car. Cardinali kept shaking his head. For the seventh time, Cardinali was going to jail. As hard as it was for him to stay away from incarceration, he never got used to it.

He was 5 foot 10 inches, yet he was so skinny that he seemed small. He had a temper, but he was also polite, and often apologized for things he said, or things he was about to say. But, in jail, he was often up against people much bigger, more vicious and had no capacity for mercy.

Cardinali’s “pod” at the Bergen County Jail was C-2, where the mentally ill were housed. There, the pod had tables with checker boards painted on, and stacks of bunk beds where the inmates slept. Many of prisoners sat at the tables, chatting and laughing like they were at a poker club. Or, they watched T.V., leaning back in their chairs and listening quietly.

Every Tuesday, counselors from Care Plus, a Wallington-based mental health treatment organization hired by the county to manage the jail diversion program, arrived to meet with groups of inmates diagnosed with mental illness. They held their sessions in a small room with storefront-sized windows, where metal folding chairs were lined in a circle. Inside the room, the cinder-block walls were pale and colorless. A television set sat there, unplugged. A bookcase was there, too. But the books were rarely red. The covers had barely a rip or fold or a fray, like they belonged on the shelves of B.Dalton, not the Bergen County Jail.

The county hired Care Plus to meet with inmates every Tuesday at 11 a.m., and each meeting was really group therapy. Counselors provided guidance to inmates and alternatives to spending their lives behind bars. Typically, 10 to 12 inmates sat in the small room, leaned on their knees and listened to each other bitch and moan about their lives.

Cardinali often walked in late, slumping in his chair, with his blonde hair leaning against the back of the chair, his legs folded and his left hand resting on his right forearm. Cardinali had to be prodded, and practically dragged in there to participate. Sometimes he was mocked and heckled because he would put up such a fuss about doing it. After several meetings, however, Cardinali started to get why the others were there: They didn’t care so much about getting better. They only saw this as a ticket out.

When he was young, Cardinali wanted to be an oceanographer. But he could never stay sober or sane long enough to get a college degree. He liked playing music better, anyway. He played drums in a band called “Omnibus.” He bumped into or played with just about everybody from the Grateful Dead, Pegasus and Quicksilver Messenger Service. When he was in Alcoholics Anonymous in Florida, Dion, the 50s rocker who sang “The Wanderer,” was his sponsor, he said. The guys who wrote “Dancing in the Moonlight,” the hit from the ’70s, penned it in his mother’s basement, he claimed.

Cardinali had a mother who was nurturing, and a father who was tough, but fair. They were basically stable, and happy, until his dad died in the mid-1980s. That was when his mother, depressed over the loss, told Cardinali that the man who died wasn’t his biological father. His real father was a jailbird, a heroin addict. He was also Jewish, which didn’t go over well with Cardinali’s Italian girlfriend at the time. After hearing the news, she broke up with him. “If you’re Italian, you marry Italian,” Cardinali remembered her saying.

Cardinali started doing heroin in the 1970s when a friend approached him and sold him a $15 bag. “I just found myself driving over to his house, in New Milford, where his family lived and I knocked on his door, like an asshole, and asked if I could get some,” Cardinali said. “And he was the one who put it in my arm the first time. I took it, and he put it right in my arm.”

For the next two decades, Cardinali was in-and-out of rehab centers in Florida, New Jersey, everywhere. Just like an addict, he promised people he’d get sober. He’d never do it again. But, he did. The more he did it, the more he ran into trouble – usually with the law. When the rehab stints failed, the jail terms started. Everywhere he went, he was intimidated, mocked and even beat up, forcing him into rages that sent him to solitary confinement.

At the Bergen County Jail, the troubles usually arose at mealtime. Another inmate would sit next to him, and slide his tray next to Cardinali’s. “You gonna eat that?” the other inmate would say. “Yes,” Cardinali would reply. The inmate would chuckle, stretch his big furry arm and grab his honey buns. “What the hell are you doing?” Cardinali would shoot back. The inmate would just laugh. He’d take a big bite out of one of them, put it back on Cardinali’s tray, and walk away.

Underneath his bed, just after lights out, Cardinali would pull himself toward the dim ray coming from the outside street lamp. He’d then reach into his sock, pull out a honey bun and munch. He’d eat while the others were sleeping. Even in the dark, where he could barely see his food, the honey bun from the sock was the best meal Cardinali got all day.

At night, Cardinali was usually more alert. During each day, the jail had Cardinali on 200 mg of Trazodone. It made him loopy, sleepy and downright numb. It was like heroin. But these drugs made him feel weak, and worthless. “I go down and crash,” he said. “I drag everybody down with me.”

In July, 2004, Cardinali started attending the jail diversion meetings. Even though he routinely showed up late – and would look half-bored as he slumped in his chair – Cardinali listened to Michael Lang, the counselor who led these meetings, and started to believe. In September, he allowed himself to be interviewed by the organization and be considered as a candidate for the program.

On Oct. 12, 2004, Cardinali was told, he’d be led into the courtroom where he’d face Judge Eugene Austin. He faced this judge before; in his prior appearances, Austin lectured Cardinali for his being a repeat offender. He gave him what seemed like the hardest, longest sentences he could give him, Cardinali said. But Care Plus assured him: This time would be different. Here, Cardinali was told, he would play by the rules, promise to continue with the therapy sessions and then, perhaps, he’d get out by Christmas.

But, on the day of the hearing, Cardinali met with his attorney, Diane D’Alessandro, who told him there was a snag. Both the judge and the assistant prosecutor told her: No rehabilitation, no deal, they said. Cardinali refused. He wanted out of everything; not just jail. He had been to rehabilitation 12 times. Each one felt like a prison sentence, he said.

The judge then delayed the hearing. “Every time,” Cardinali said at the time, “I have my expectations high, and they’re dashed.”

About a week later, Lang went to see Cardinali. It was about 1 p.m. Cardinali, up late because he was eating his honey buns in bed, had been taking a nap. He sat up in his bunk, groggy, and rubbed his eyes.

Lang told him that his records were reviewed again. The organization decided, after some painful consideration, that he was too much of a risk. He would not be a successful candidate, he was told, because of his history of relapse. He would not be allowed to go to therapy sessions.

Cardinali pleaded for a second chance. “I’m sorry,” Lang said. Then he got up, and walked away.

When the therapy sessions stopped, the inmates got worse. In December, the same inmate who stole his honey buns swiped a pen from another prisoner, walked over to Cardinali and started lunging at him. Cardinali got into his Tai Chi pose, the same one he used on the police back in July. A sheriff’s officer saw him raise his leg and ran over and wrestled Cardinali to the ground. They grabbed him under his arms, and brought him to the 8-by-10-foot lockdown room, where he stayed for three days.

While in there, Cardinali called his mother collect. It was a brief conversation. He was yelling so loudly, and he sounded so desperate, that she hung up. He tried to call back several times, but she wouldn’t accept the charges.

“She’s so depressed. It’s fucking a drag,” he said at the time. “She don’t sound good.”

The jail psychiatrist, meanwhile, increased his medication, making Cardinali feel loopy. So he got the psychiatrist to change his medication, switching to half a milligram of Prozac. It was a lot better than 300 milligrams of Trazodone. Cardinali thought Trazodone fried his brain worse than any street drug ever did.

By the time Jan. 28, 2005 came, Cardinali understood what he was going face: The whole court hearing would be a formality. The temper that flared up in December – the same one he kept in check when he first got to jail, back in July – would do him in.

Then, finally, a break: Days before the hearing, Cardinali’s attorney got the word: A back ailment forced Judge Austin to retire from the bench. He would instead get Lois Lipton, a former Family Court judge who talked in a quiet, but reassuring voice, sounding more like a counselor than a judge.

In the early morning, Cardinali got up, combed his hair, slipped on a pair of glasses, faced the sheriff’s officers and extended his arms. They cuffed his wrists, and chained his ankles. Then they boarded the van for the courthouse. He rode the elevator to the third floor, and sat in a small room with bars. His attorney, D’Alessandro walked in, carrying his case file. It was the first time he’d seen her in weeks.

“I’m going to see if I can get your released today,” she told him.

Cardinali nodded. Then a sheriff’s officer opened the gate, clutched Cardinali’s arm, and led him to the courtroom. He shuffled slowly, the cuffs on his legs impeding his movement.

Cardinali walked up to the table, and stood next to his attorney.

“Counselor, do you have anything?” the judge said.

“Yes, your honor,” D’Alessandro said. “Mr. Cardinli agrees to the terms of the plea … But, if I may, your honor – ”

“Yes?”

“My client has been in for six months now,” she said. “It appears to me that people with similar offenses typically spend six months – not 12 – in jail before they’re released.”

Cardinali stood silently as D’Alessandro talked, and told the judge he wanted to make something of his life. He’d been involved in Care Plus, she said, but said nothing about him being thrown out. He’s in Alcoholics Anonymous, she said, even though he hadn’t been to a meeting since before entering jail.

Most importantly, D’Alessandro said, he would have a place to live, though she didn’t say where. He would also have a ride, but she didn’t say who would provide it.

“The criminal history concerns me,” Lipton said. “There’re been a lot of disorderly persons offenses that seem to go on and on. …Regardless of that, I am going to impose a 184-day sentence, including time served.”

“Excuse me, your honor,” his attorney asked. “One-hundred-eighty-four days – that means he can be released today, your honor?”

“That’s correct,” the judge said, then turning back to Cardinali. “I believe you are trying to help yourself. But a condition of your treatment is to continue psychiatric treatment and AA meetings.”

“Yes, your honor,” Cardinali said.

His shoulders dropped. Started, his mouth was agape. He struggled with his emotions, not knowing how to feel. Then, impulsively, he managed a broad smile.

Three days later, Cardinali was tired, hungry and feeling a little needy. Already, he had had it with the shelter food, which was only slightly better than what he had at the jail, as well as sleeping in cold trucks and crowded shelters.

He called a friend, who took him to the Cedar Lane Diner in Teaneck, where he had his best meal since July. After that, Cardinali begged to go to Palisades Park. “Please, I’ll do anything,” he said. “Just this once. I’ll never ask again.”

A half hour later, they arrived there, pulling into a parking space next to Hana’s Music. A light dusting of snow started to fall as they got out of the car, and walked into the store. Once in, Cardinali brushed the snow off himself.

Cardinali then started walking anxiously around the store. He looked at one wall, and then another, and then another. Guitars hung from all of them. He saw a Les Paul hanging on the wall rack, behind a piano. He picked it up, pulled out a stool, set it on his knee and strummed.

“I can play anything I can hear,” he said. “What I mean is, I can hear the notes. Can’t read ’em.”

He launched into “Just for Love,” by “Quicksilver Messenger Service.” Cardinali liked Quicksilver. The band sang about love and heartache, but never in a way that made you sad, he said. He sang every word and strung every note like he was 20 again. His chapped fingers, peeling around his finger nails, didn’t betray him. The song moved along, and Cardinali, again, smiled, showing off his big, white dentures.

Just about love, like the wing of some high-flying bird, Of the songs I will sing to you, you can hear every word,

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

3:19 AM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: COPING with bipolar disorder, COPING with general mental health issues

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

Homeless in America: Hope amid Hopelessness

Robin Reilly picked at her chef’s salad, frowning at the sight of the wilted lettuce, Every so often, she fiddled with it with her fork, only to gently place down her silverware and dismiss it with her hand. Lou sat across from her, taking big, mouth-sized bites out of roast beef that was piled two-inches thick between two slices of rye bread. Reilly managed a thin smile as she watched Lou eat and smudge a drop of mayonnaise on each corner of his lips.

Robin Reilly picked at her chef’s salad, frowning at the sight of the wilted lettuce, Every so often, she fiddled with it with her fork, only to gently place down her silverware and dismiss it with her hand. Lou sat across from her, taking big, mouth-sized bites out of roast beef that was piled two-inches thick between two slices of rye bread. Reilly managed a thin smile as she watched Lou eat and smudge a drop of mayonnaise on each corner of his lips.

Seeing Lou eat, or do anything that’s good for his body, always boosts Reilly’s morale. She has to coral him to go to the Heritage Diner in Hackensack, where she takes people who are homeless - or, like Lou, formerly homeless - and buy them a good meal. Unlike a lot of people who know Reilly, Lou rarely goes hungry. His belly is too full with cooking wine, but not what used to be his favorite drink, mouthwash. He drank Listerine because, like the wine, it was cheap, but it made his moods swing so much that he picked fights with people a the bus terminal, at homeless shelters and sometimes even with Reilly. He’d yell at her, curse at her, and once threw a punch at her, even though Reilly is doing everything to keep Lou alive. Drinking mouthwash earned him the nickname, “Listerine Lou.”

But on this February day, Lou felt emboldened. “Today’s been a very good day,” Reilly assured him. “We got some very good news.” The doctor said Lou’s PSA count was down from around 60 to 4. The prostate cancer that has already spread to his bones and lymph nodes appears to have finally slowed, thanks to hormone therapy. He’s 58, and recently got into subsidized housing after two decades on the streets. But he knows he doesn’t have much time left. The possibility of adding even a year to his life expectancy, after suffering for years as an unemployed alcoholic, is the best news he’s had in decades.

Reilly always has Lou’s back. Even when he becomes the Hackensack version of Mr. Hyde, Reilly provides a comfort zone for Lou when everybody else cuts and runs. She transports him to Bergen Regional Medical Center in Paramus for checkups. When Lou, who declined to give his last name, used to spend his nights sleeping in rental-trailers at the Budget Rental Car on River Street, Reilly always got him clothes and a blanket. Recently, she bought him a Yankees when cancer treatment took away clumps of his hair.

This is Reilly’s daily cause, the kinds of things she does for the hundreds of others she’s pulled out of gutters, bushes alongside the railroad tracks and, on occasion, picked them up from jail before transporting them to the nearest shelter. Seeing them achieve any kind of success – whether it’s someone finding housing, or someone who just survived a medical nightmare – turns Reilly, 66, into a bubbly school girl. She’ll talk fast and gleefully whenever, on the rare occasion, someone among the hundreds she’s helped has found a way to move off the streets and move away from the booze.

“I just took a man out of the street, and then I took him to the bank, I took out money from the ATM. Then I took him to a hotel,” Reilly said. “We’re all about doing God’s work through our actions.”

But as excited as she was for Lou, and the many others she’s helped, Reilly is finally tired. Not tired of her work. Saving people from cold weather that leaves them frostbitten never really gets old. She’s just tired of getting jerked around by the city, the police and even other homeless advocates who, she believes, don’t consider her work legitimate. She’s tired of people calling her “a homeless advocate without a home.” She knows its true, and she doesn’t blame people for saying it. She’s just he’s tired of fighting a system that refuses to bend.

Every homeless shelter or drop-in center she’s operated in Hackensack, N.J. over the past decade has been closed because of code violations, or because she's had run-ins with city officials, police, religious clergy and other homeless advocates. Every job she’s had dealing with homeless advocates she’s left in frustration because, from her point of view, they never do the job good enough. Sometimes, she thinks just like the people she pulls out of the alleys and gutters and tries to help. Don’t get your hopes too high, she says, because the disappointment will be worse.

The latest eviction came in December at the 300-year-old First Reformed Church in Hackensack, where she ran a three-day-a-week homeless outreach center. She thought that was it. This would be the end of yet another stint as an “advocate without a home.” She had a place for people who are usually too drunk, mentally ill or drugged up to get into the local county shelters. Many of them don’t last long in life, unless Reilly is there with her safety net of care.

Months back, she prayed to God, hoping there would be one more place that would give her chance. The church came calling, and Reilly saw this as a sign from God that this was her last, but best possible resort.

Then she threw a Christmas party for the homeless and, according to the church, didn’t follow the rules. She served food before the pre-dinner sermon was finished, and then protested loudly when the church made the group of about 100 hungry people and staff members stop eating and serving. The eviction came swiftly; the church, which was already under pressure from city officials who have wanted her out of Hackensack for decades, ordered her to leave in a week.

Now she wonders if God has another plan for her, whatever that is. Maybe God wants her in the streets, being with the homeless and away from the bureaucrats, the politicians and the others who, she believes, stand in her way. She’ll now pursue this mission with the same vigor she’s had before – even if that energy, combined with a strong will that often becomes stubbornness, is what always gets her into trouble.

“I get tired of fighting the system. I get tired of fighting everybody because it’s not going to get better,” she said while still fiddling with her lettuce. “But, what do you all day? Knit? What else am I going to do?”

Just weeks ago, she found a long-time member of her homeless family, John, partially “frozen” and literally “stuck” to a sidewalk, she said. His body temperature was around 76 degrees.

John, whose last name Reilly did not want to divulge, has been been in the street for decades. He's been on life support systems. He’s had episodes where he’s excreted nothing but blood. Every time, Robin’s been there to take him to the hospital, usually to the Hackensack University Medical Center. Each time, he’s emerged just days later, alive and as well as he could be, before returning to the streets, the booze and the heroin that eventually brings him back to the hospital.

But with a sub-zero wind chill turning Hackensack’s streets into lifeless alleys, Reilly thought, for the first time, that John's hard-scrabble life was finally over. She took his pulse, and couldn’t feel one. He could have been dead, but he was too cold, so it was impossible to tell. She called for an ambulance and got him to a hospital, as she always did.

Within a week, he was sitting up in his bed and talking. Now he’s out again, walking the streets and surviving as he always does, but staying within arms reach of Reilly.

“I don’t want to get a call anymore, saying, ‘We’ve got this frozen guy. Can you come out here?’” she said. “I don’t want any more calls like that.”

Reilly’s convinced that if she wasn’t out there scouting the neighborhoods, looking for people lying along railroad tracks, she wouldn’t have found him. One of the luxuries of working out of her car is that she can be a one-person search-and-rescue team. She knows where all the hiding spots are. Besides the homeless themselves, she’s also the first person people go to – including those who give her a hard time, like the police – when they want to get help for someone, or themselves.

In the months prior to moving to the church, Reilly was doing the same thing, riding around Hackensack, dishing out food and water and giving homeless people a chance to cool off from the heat by sitting in her air-conditioned car. She had been thrown out of her State Street outreach center in June because, according to city officials, she was breaking the law by feeding homeless people on site. They were also “closing their eyes” on her couch, police said – the same couch she’s dragged with her wherever she’s gone to set up her advocacy work.

To Reilly, this was perhaps the most traumatic closure she’s had to deal with. She had been at the State Street site in Hackensack for seven years, by far her longest stint. Usually, she lasts anywhere from three months to no more than a couple years at any given place.

For those three months after her State Street departure, she did what she's doing now, which is what she's always done between stints. One of her “lieutenants” – a sixtysomething man with a dark blue knit cap and a scraggly gray beard known only by the name of “Coach” – scouts the neighborhoods carrying a cell phone, looking for people who were wasting away. He’ll call her, and then she’ll drive 10 miles from her Oradell home, and find them. Then she usually drives somebody who was on their deathbed to the hospital, or calls and ambulance, to get medical assistance.

Since getting thrown out of State Street last year, most of them have lived; some of them haven’t. In the last year alone, four died before Reilly was able to get to them and give them assistance. In the meantime, Reilly has lost weight. “I’m sick – sick with worry,” she said last year, about 40 pounds lighter than she as three years ago. She's never lost this much weight before.

The First Reformed Church gave her fourth place in a decade, and granted the space that opened to the public on Oct. 23. It was the kind of place she had been kicked out of before – an old church that’s part of the city establishment, where some members have been attending for 90 years.

It’s also the kind of place that’s given Reilly a chance in the past, such a church-based homeless shelter called “Peter’s Place” that employed Reilly as a homeless advocate nearly a decade ago. Usually, at these types of places, Reilly’s self-described demands to put the homeless first run afoul with management, she said, and she finds herself out in the street again, pulling the homeless into her car.

Before State Street, she operated out of a 12-by-20-foot office at the nearby Salvation Army and provided assistance to more than 1,100 homeless and poor people. The place was only temporary, but she attracted the same of legion of followers who always come to cry on her shoulder or sleep on her couch. They're the same people who have stuck with her since she was an administrator at Peter’s Place. In just a few months at the Salvation Army, she referred hundreds of clients to hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and employers.

"I'm not working for anyone right now. I'm working for God," Reilly said in 2001 as she packed furniture, a sewing machine, and cans of food and prepared to move. Several homeless people watched, and they hugged her when she grew misty-eyed.

Before Peter’s Place, Reilly was an interior designer who decorated medical facilities. Back then, she dabbled in homeless causes, and she was so moved by the people she met that she gave up her lucrative career to become a full-time advocate.

When she worked at the Hackensack University Medical Center, she had an opportunity to see the problem, for the first time, up close.

She saw people with missing toes and thumbs hauled in on stretches, quivering after spending the night in below-freezing temperatures. She saw them arrive with no one standing by them as they were hauled off to the ambulances or wheeled in on wheelchairs.

It brought out her aggressive spirit that has helped her prevail for so many years. It brought out a side of her that is only witnessed by people who stand in her way – such as Bergen County Community Action Program, the county homeless agency that she calls “a toothless bureaucracy” and, in her view, doesn’t do enough to help.

Reilly doesn’t worry about her image, either, because she’s more than an advocate, she says. She’s a diplomat and an ambassador for a homeless population that numbers in the hundreds in Hackensack, largely because the city is the Bergen County seat and, therefore, offers county-sponsored welfare services. In public, she’s shown herself to be as sweet-as-pie, one who is not afraid to curry favor with the media and present herself as maybe the one person who actually makes an effort to take care of the homeless.

Mostly, though, Reilly is a self-described “rebel,” and that’s what she’s most proud of. Rebels, she believes, make the best advocates. They don’t worry about what could happen to them, she says, because that kind of worry only impedes progress. They get things done because they’re not afraid of pissing people off, she says, and she’s done a lot of that.

Some of the homeless and poor, as a result, consider Reilly their guardian angel. Unlike the local county homeless agency, the Bergen County Community Action Program, she takes people who are in every condition – drug addicted, alcoholic or on the brink of death.

Many of them, like Lou, had decent paying jobs at respectable companies. Lou worked for Bell Telephone when drinking and the early 1990s recession threw him out in the streets. For nearly two decades, he’s been licking his wounds over this. Reilly was his only safety net. “This was supposed to be a permanent job,” said Lou, who worked at Bell as a technician. “I thought I’d be there forever. I thought I’d be getting the 40-year pin by now.”

Hackensack city officials, the First Reformed Church and representatives of Bergen County CAP declined to respond to this article. But they’ve spoken publicly before, saying they consider Reilly an “enabler” who allows the homeless to continue their self-destructive ways without giving them a healthy alternative. They also blame her for breaking rules too often – as the First Reformed Church claimed when they threw out in December after just two months.

While she has plenty of detractors, she has hundreds of supporters. Many of them are homeless, obviously, who have followed her around for years, and they know that wherever she is, their chances of getting food, guidance and a sense of morality have improved.

Some of the people she’s cared for have died, but many more have lived. At the First Reformed Church, she hoped to save hundreds more – at least that many – as long as she could stay on her feet, maintain good health and keep doing what she’s famous for in the Bergen County, N.J. area.

“’You’re going to put us on the map,’ they told me," Reilly said. "‘You’re going to put us on the map. They were not ready for the city. They said, ‘Don’t worry about it.’ I said, ‘Maybe you should worry.’"

At the October event, Reilly faced about 75 other homeless advocates and people without a home – many of them mentally ill or substance abusers, but nearly all of whom were refused care at the county homeless shelters. The event was peaceful; but it also attracted publicity in the local media.

Just days later, city code officials warned the church that Reilly was breaking the law, she said. Reilly claims the city’s call for upgrades seemed impossible to satisfy and seemed to have nothing to do with homeless outreach – such as installing a new sprinkler system.

Reilly began to worry again. The church, however, told her not to. “They said, ‘We’ve been in this community forever. We know how to handle them,’” she said.

But over the next two months, Reilly heard nothing about the city’s gripes, which made her worry even more. She asked the church again, and got the same response. Not to worry.

The end came on Dec. 21, when Reilly treated the homeless and the poor to a Sunday Christmas dinner. Reilly got upset when the guests had to sit through a 20-minute sermon before being served Christmas dinner. The Rev. Timothy Ippolito, pastor at Faith Reformed Church in Lodi, was quoted in The Record of Bergen County, N.J. as saying that the worship service was “first and foremost for the community of Hackensack" and feeding for the "economically disadvantaged" would begin after the sermon. At one point during the service, the newspaper said, the food servers were told to "drop" their utensils. Reilly said Ippolito threatened to call police if she interfered with the sermon, an accusation Ippolito later acknowledged, according to the article.

Reilly "sabotaged the agenda," said Ippolito, adding that he gave Reilly an "itinerary" for the night before the gathering and described Reilly as "another example of someone who likes to buck the system," he was quoted as saying in The Record.

Tempers flared between a church member and one of Reilly’s lieutenants. Reilly interceded, and said the sermon was interfering with what God intended. “You’re of here, Robin,” the man said, according to Reilly and others who were within earshot. A week later, Reilly was packed up and gone.

Outside of her car, her favorite place now is the Heritage Diner, where she’s treated countless homeless over the years to lunch and dinner. There, she gets a chance to talk to them without worrying about whether she’s violating a city code, or if she has enough time to pack her belongings and move to another place. Over wilted lettuce, she gets personal one-on-one time that’s almost impossible to get when she’s running a busy shelter or outreach center, and catering to the needs of hundreds of people who are tired, cold, hungry and wet.

She still hopes that she someday, finally, will find a place that won’t kick her out. She dreams of just the perfect place, with the perfect city administration, police department and local support to make it work.

For now, however, chatting about PSA counts over wilted lettuce will suffice.

“Nobody ever knows how to get rid of me,” she said.

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

2:43 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

Mental health in the media

I've heard a few people recently say that the only profession that's doing well in this recession is journalism.

I've heard a few people recently say that the only profession that's doing well in this recession is journalism.

Forgive me for nearly laughing but, whenever there's a recession, history has shown that the media are among the first casualties.

What's hurting it now is that the profession, ironically, has not adjusted well to the new media age. Advertising revenues have fallen dramatically, and classifieds have virtually disappeared from news pages. Thank you very little, Craig's List.

But other factors have come in to play. Take the case of Peter Sigal, an editor at The New York Times, whom I interviewed recently for my graduate work at Columbia University. Here's his story:

Peter Sigal took a break on a couch at The New York Times, his face flush and his greased, and his curly hair pulled up and out.

That’s what happens when you run your fingers through your hair so many times, he says, worrying about subject-verb agreement or whether Sarah Palin’s name is spelled right. He’s surprised that, at age 40, he hasn’t pulled all of his hair out.

But Sigal still gets a charge out of being a copy editor despite his hectic lifestyle, increasing workload and financial pressures he faces as the news business shrinks – and what’s left of it moves to the Internet.

“It’s still a challenge,” said Sigal, a father of two who is deputy slot editor on the Times’s national desk. “You still get an adrenaline rush at deadline. You’re working at a paper where you’re making a difference.”

He enjoys serving as what he calls “one of the last eyes” on stories printed in one of the world’s most respected newspapers – even if the unpredictability and the instability of the news business, as well as the infighting and occasional crisis that affects the Times can, at times, prove to be embarrassing.

One such case involved the Times’ failure to properly supervise a young journalist named Jayson Blair, who plagiarized and fudged facts and information and stories over a five year period. Most found the saga demoralizing; he views the exerperience as educational that led to greater oversight and strengthened the newspaper’s overall quality.

“That was a failure on so many different levels,” said Sigal, who occasionally edited Blair’s copy after he was hired by the Times in 2003. “The guy wasn’t submitting receipts from the days he wasn’t supposed to be traveling.”

Sigal stays positive even as he earns what considers “low pay” for a five-day-a-week, 4 p.m.-to-12 a.m. job while fathering two young children with his wife – an Associated Press journalist who works a 6:30 a.m.-to-3:30 p.m. shift – and doing daily babysitting hand-offs with her.

“My wife and I are doing it the hard way,” he said.

He helps run a desk with that has a daily complement of anywhere from 10 to 18 editors at a time, reviewing everything from the broad – such as story placement and headlines – to the minute detail – such as spelling, style and factual mistakes.

Their mission is to check for libel or anything else that slips by the backfield editors, who serve as the first eyes on stories, edit for content and “make sure the story they got is the story they wanted, and that it makes sense,” he said.

Once the backfield editors’ work is complete, Sigal’s copy desk can pay closer attention to the smaller details of stories and “look at the stories as a page and say, ‘This headline is wrong,’” he said. “They can keep a closer look on errors.”

“The editors edit the stories, then send them to me [or the slot editor] with headlines on them and I check to make sure they fit with the story,” he said. “I’ll rewrite them if they don’t fit.”

Times are changing, however. The New York Times recently had a round of buyouts, and his copy desk has lost some copy editors along the way – though he’s not sure how many.

Each editor has assumed more responsibility, forcing them to work harder to ensure accuracy. The size of the paper is shrinking, too, as a way to save money. As a result, Sigal said, they edit smaller stories, but there are many more of them.

On one September day, his desk had to edit 25 stories in an hour “and a lot of them were 400 or 500 words. In the past we had fewer slugs and longer stories – we had 1,000 1,500 word stories,” he said.

“We have to do more and more with less,” Sigal said. “We don’t have the luxury of middling for four of five hours on a 1,000-word story.”

He spends much of his day sitting in a field of desks that resembles an orchestra – he calls it “the rim” – that encircles him as he assigns stories to editors. But the action is fast and the tension can be thick.

In his role as a deputy slot editor, Sigal has to keep an even closer eye on words and phrases, and he shoots for “economy” in the story phrasing so that the same point can be said with fewer words.

He has to match editors’ skills with certain stories – and in a 24-hour continuous cycle that has constant deadlines for an increasing number of stories, he has to decide quickly.

Some editors work better than others with a complicated investigative piece, he said. Others work better and faster on deadline. Either way, it’s his job to choose who does what, and not worry about who may be offended.

“I’m paid to be a critical thinker,” he said. “You can’t be afraid of hurting feelings.”

Many of these decisions have to be made thoughtfully but quickly – particularly when a breaking news story must move immediately to the web. Some copy editors have been arriving as much as four hours earlier to work – as early as 1 p.m. – to start making decisions on what stories get edited, and when

“A lot of what we do is being like a traffic cop,” he said.

The pace can get especially hectic when stories come in late.

For a newspaper like the Times that covers stories spanning several time zones, lateness is commonplace. Working directly with reporters to ensure that stories are accurate, clear and focus, he says, becomes even more critical.

“We are encouraged to call the reporters directly,” he said. “We’re encouraged to send them playbacks [reading the story to them] for stories we’ve edited, and the reporters expect it. In the slot, we basically demand it.”

“If a story comes back to me in the slot and the lead doesn’t support the story, then I’ll tell copy desk to redo it and we’ll go back at it,” he added.

Each decision, however, must be made as a team, he says.

Copy editors have to develop partnerships not just with each other, but also the reporters. While their names are not on the stories, he said, each article has the copy editor’s imprint.

If a lead to a story doesn’t work, copy editors shouldn’t be afraid to contact the reporter, suggest they rewrite it or, if they balk or fail to do it, the copy editors will rewrite it themselves.

“Copy editors are equal partners,” he said. “You have just as much right to correct or change a lead as anybody else.”

The hardest part of the partnership is developing trust – particularly as the evolving, 24-hour news cycle forces copy editors to work more with less, Sigal said. Getting inside a reporter’s head, he said, is impossible when the pace is moving fast, and the time for a deep analytical edit job is short.

The Jayson Blair controversy, for example, was an example of a “failure of supervision” and partnership that has become more common as the news industry gets smaller and “we’re being asked do more and more with less,” but the demand for immediacy is greater, he said.

In Blair’s case, he says, there was too much trust. Though he wasn’t promoted to the deputy slot position until 2005, Sigal takes partial responsibility for the failures.

“I remember talking to him one time – he filed two stories from Virginia Beach and another from Montgomery County, Md.,” Sigal said. “I called him and I said, ‘Jayson that’s pretty far. How did you file these two stories?’ He said, ‘Oh yeah, man. I finished that one in Virgina, I got in my car and jammed up.”

“In hindsight, he was probably in Brooklyn the whole time,” he said.

Sigal ultimately was forced to copy edit the 14,000-word “correction” the Times did for Blair’s articles – a task that took 17 hours for himself and another editor to complete.

Such work stretches him thin – and makes him wonder whether he’ll put up with the erratic pace of the job once his his children, who are 2 and 7 months old, are older.

But he and his wife have managed to still love the profession enough that they make sacrifces in order to survive in it – even though they rarely go on vacations together and can’t afford daycare.

“She was in Iraq last fall and she was six months pregnant,” Sigal said of his wife. “We have a little bit of a challenge.”

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

7:10 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

Getting the public to pay attention to postpartum depression

Postpartum depression is getting a public airing.

Postpartum depression is getting a public airing.

ABC television network's "Private Practice" series is supporting postpartum depression awareness efforts by showing an episode on Feb. 12 with a storyline on the topic.

ABC also consulted with Postpartum Support International to create a public service announcement about postpartum depression, which will be available on the network's website immediately following the show. Contact information for Postpartum Support International can be found.

While the episode has not been seen prior to airing, postpartum depression advocates are hopeful that the material will "closely correspond to the clinical presentations women experience when going through postpartum depression."

"Storylines which responsibly present the ravages of these illnesses without the alienating sensationalism - which fuels stigma rather than hope - can greatly influence a nation's response to those suffering from these illnesses."

Susan Dowd Stone of Postpartum Support International thanked ABC for its willingness to not only approach this critical subject matter, but to offer viewers contact information to Postpartum Support International, the world's largest nonprofit devoted to the eradication of perinatal mood disorders.

"This ensures that those moved by the shows content will not be left wondering where they can go to find help for themselves or a loved one," Stone said.

"This year, as we seek to finally pass The Melanie Blocker Stokes MOTHERS Act,we are grateful for the educational outreach offered by such leading networks in our fight to eradicate the needless suffering of the over 800,000 women who will experience a perinatal mood disorder this year," she said.

Posted by

Tom Davis

at

3:34 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()